More Talk, Less Hock #2: Heywood Gould

A funny thing happened after I launched the new “More Talk, Less Hock” writer spotlight on my blog a few weeks back. Someone took me seriously. To be honest, I really didn’t think there was going to be a “More Talk, Less Talk #2.” #1 was going to pimp my buddy Russel D McLean, and that would be that. But then I got an e-mail from a publisher pitching an interview with another writer — a non-buddy, someone I’d never met — and I thought, “Why the hell not?” So I said yes.

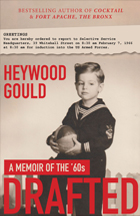

I’m glad I did. Heywood Gould is one interesting dude. I mean, how many writers have you met who’ve not only met Michael Keaton, they’ve directed Michael Keaton movies? The guy wrote Cocktail, for chrissakes — the movie and the book! (Yeah, I didn’t know it was a book, either.) Heywood’s newest novel is the wild chase-thriller The Serial Killer’s Daughter. Here’s what he and I had to say to one another.

Me: Back in the day, you wrote the screenplays for some pretty memorable movies. The Boys from Brazil. Fort Apache, the Bronx. Cocktail. So when I hear you’ve got a new thriller out, I get the sneaking suspicion it began life as a screenplay. How far am I off the mark?

[Aside: Quite a bit, it turns out.]

Serial Heywood: Writing a spec screenplay is like shoveling manure for three months and getting paid with a lottery ticket. I’ll never do it. The book was inspired by a story I read about how a suspected serial killer was caught by matching the victims’ DNA with his daughter’s Pap test. I had always wondered what happened to the families of these monsters. How did they live in a town where Dad had wreaked havoc? There was never any follow-up on the families of the victims. How were they dealing with this sudden intrusion of evil into their lives? Also, a la Hitchcock, I wanted to take an ordinary guy, in this case a nerdy movie buff, who lands the one girl he never thought he could get, and then has to run for his life.

Me: Whoa. Seeing as I was so incredibly off with my first guess, there’s only one thing to do — make another one. Is it safe to assume you can relate to “nerdy movie buff” types? You had quite a run in Hollywood as a writer/director. I can only assume you had the gumption it takes to make that happen because of a deep love of film.

Heywood: Busted! I am the original nerdy film buff. Movies were a rainy Saturday diversion until I was 15 and discovered a little theater in my Brooklyn neighborhood whose crotchety owner showed old comedies (Keaton, Chaplin, Fields, Marx Bros., Stooges, etc.) and Warner Bros. antiques (Cagney, Bogie, Edward G.) I was hooked. Still am. I can see the same movies over and over. It’s like reading the Bible — you always find something new. Manhattan in the ’60s had at least 10 theaters that showed old Hollywood or foreign films. It was the era of Fellini, Antonioni, De Sica, Bergman, Godard, Truffaut, Chabrol, Reed, the Boulting Bros., Kurosawa, etc. Every week brought another revelation. The Apollo in Times Square showed triple features. We’d get meatball sandwiches and spend the night. You could see great films, wash your socks and score a little cheap weed. The balcony smelled of garlic, dirty feet and stale tobacco. Suggestive moans and groans came from the last seats. We kept our eyes on the screen. I read Film Quarterly, Sight and Sound, Andrew Sarris in the Village Voice. It all seemed so far away and glamorous that I never thought I could ever be a part of it. I wanted to be a cynical reporter like Ben Hecht or a suffering novelist like Fitzgerald. Tragic artist was my pimp. I thought a little alcoholism plus a touch of T.B. a la Orwell was just the ticket for getting the girls. Boy, was I wrong.

Me: So how’d you go from being a Brooklyn film nerd to a published author and a Hollywood writer/director?

Heywood: That’s War and Peace.

1947: A blizzard in Brooklyn. I’m 5. It’s warm in the kitchen. My mom does freelance typing at the table. She leaves a page in the typewriter and gets up to make lunch. I move into her seat and start to bang on the keys. It’s the first piece of clean commercial work I destroy.

1951: I’m 8 1/2. A big, fat 10-year-old slob is bullying me, taking me into the stairwell of our building and putting me in a choke hold until I promise to bring him a dime, which I steal from my mom’s purse. Promises to kill me if I tell, and I believe him. I write a story about a machine that magically appears and helps a boxer win a big match. I disguise the characters so my parents won’t recognize the bully.

1956: I’m graduating from Public School 154. I write an essay about what the future holds for our class. Make a few jokes about my friends getting arrested, me getting drunk and falling off the Ferris Wheel in Coney Island. All my friends think this is uproarious. The teachers don’t agree. I don’t win the English medal.

1959: The high school literary magazine snubs me because I’m on the basketball team. I win a fountain pen in a citywide contest for writing an essay about They Came To Cordura and Northwest Passage, both of which became pretty good movies. I get the pen, but no respect. My English teacher asks me one day, “Are your parents immigrants?” When I ask why, he says, “All immigrants use too many adjectives.” He advises me to forget writing as a career. “The prize was an aberration,” he says.

1960: The college literary magazine rejects me. “I don’t have the time or the inclination to tell you all the ways that this is inferior,” says the editor. I have violent sex dreams about her. Still do.

1962: A newspaper strike lasts for seven months. When it’s over, the New York Post has no copyboys. I write a letter to the managing editor. I have just spent nine months in France trying to be Fitzgerald. I mention that I speak French. His wife is French. He has the personnel manager call me for an interview. “We’ll put you on a tryout basis.” My first day the managing editor yells at me across the tundra-like city room: “Apportez-moi un cafe et un bagelle avec fromage de creme.” [Translation: "Get me a bagel with cream cheese."] Ever the wiseguy, I answer, “C’est une bagelle.” [Translation: He corrected the managing editor's French.] Thank God they like wise guys in the newspaper business. He laughs and I’m hired.

1963: Kennedy is assassinated. I work the whole weekend in the wire room. It’s a national tragedy, the country will never be the same. I’m thrilled to be working on the biggest story of the year.

1963: I’m given a three-month tryout as a reporter. I cover Mafia hits, civil rights, cool burglaries, gory murders. I’m sent to a Spanish class for police officers. Thirty red-faced Irish cops squirm angrily while a nice Puerto Rican lady teaches them rudimentary phrases so “you can communicate with the community.” All the six papers and three networks are covering this love fest. But I’ve been around cops for two years now. I know this is too good to be true. David Halberstam of the New York Times, back from being expelled from Vietnam by the U.S. Army, is covering, complete with clipboard and assistant. When he decides there is no story he leaves and is followed by the entire press corps. I make myself small in the back of the room. The cops reach critical mass. “Why do we have to learn Spanish? Why can’t they learn English?” “These people are animals. See the way they throw their garbage on the street?” “When some junkie pulls a knife on you, you don’t have time to pull out your dictionary.” I take it all down. Next day I scoop the city. I’m hired.

1963-65: I’m a 20-year-old with a press card that gets him in anywhere in New York City. I cover MLK’s “I Have a Dream Speech” in D.C. Also the rise of Malcom X and the Nation of Islam. The anti-war movement, demos and sabotage. Harlem erupts in riots. Then Newark and Elizabeth and Paterson, N.J., explode. Break a story about rats infesting a Harlem housing project. Ride with civil rights activists trying to stall cars on New York’s highways to prevent the opening of the World’s Fair of ’64. Great idea, but nobody shows up and the fair is a big success. A California surfer breaks through the skylight of the Museum of Natural History, going under and around the electric eyes, and steals the Star of India, a huge sapphire, providing the inspiration for Topkapi. An epidemic of fat dentists drugging and raping their patients. Seems they have a club and a newsletter. A spoiled Park Avenue scion kills his girlfriend and rides around for days with her body in a blanket in the back seat of his ’56 Jaguar convertible. Mafia Don Frank Costello arrested for vagrancy. Flashes a wad of hundreds and the judge laughs as he dismisses the case. Occasionally on the 4 to 12 shift I’m a leg man, picking up quotes and items for Earl Wilson, a syndicated gossip columnist (604 papers around the world). I sit at the press table in the Copa, drink Chivas, smoke Camels and hear Sinatra, Nat “KIng” Cole, Vic Damone, Joe E. Lewis, Sammy Davis Jr. The Latin Quarter, another famous nightclub, has ten “leggy chorines,” 6 feet and taller. I’m tall, trim and 20, look good in my suit and have a fund of witty (at least to me) repartee. Plus, I’m making $95 a week. But they go for the short, fat and 50 guys, pinky rings and big cigars, look exactly like they do in every movie. Hard to tell who’s imitating whom.

More stories. The South Bronx is a war zone. Drugs, street crime, grinding poverty. An occasional short, fat 50 guy is found in the back seat of a Caddy with a bloody hole in his head, cigar between his fingers. A Chinese crew mutinies on a docked Greek freighter. I sneak on board pretending to be a doctor. I will go anywhere, do or say anything to get a story. There are six newspapers in the city and I want to scoop them all. I live in a sub-basement on Barrow Street in Greenwich Village. Fifty-three dollars a month. I eat myself into a stupor in Chinatown for three dollars. (If you don’t believe me ask someone who was there.) It’s too good to last.

February 1966: I’m drafted.

1966-68: A roaring darkness descends over the world. I discover the “control class,” people whose only skill is to acquire power over others. I will spend the rest of my life scuttling out from under their hobnailed boots.

1968-69: I surface from a weird dream to discover I have a wife and a baby son. Somehow I convince IBM that I’m the head of a cutting-edge media company. (See Corporation Freak.) I play basketball on LSD and dominate. One of my teammates is the story editor of a TV show called N.Y.P.D. I tell him some of the stories I covered as a reporter. He brings me to David Susskind, the biggest TV producer in New York. Susskind is eating a corned beef sandwich and working three phone lines. “Sure, give him a script,” he says. I’m so green I put quotation marks around the dialogue. Nobody cares. I get loaded at the Xmas party and puke all over Susskind’s desk. Next day, I slink in to apologize. “That was some party, huh?” he says. “Were you around when that hooker chased Jack [Warden, the star] around his trailer?” Ah, the good old days.

1970: N.Y.P.D. canceled. All the writers go to L.A. I stay in New York because I’m going to write The Great American Novel. I write for Stag, a men’s magazine. Make up news stories like “Diving for Nazi Gold Off the Florida Coast,” “Rabbi Officiates At Lesbian Wedding.” The editor-in-chief is Mario Puzo. I write porno novels, five bucks a page. Ghost write books on Swedish massage and college basketball. Write a biography of Sir Christopher Wren. A medical book called Headaches and Health. Anything that pays. I play poker to make the rent. Finally have a losing night and have to borrow from a shylock who lurks around the edges of the game like a jackal around the campfire. Can’t pay him back and the vig is mounting. He knows if he breaks my legs nobody will borrow from him so he gets me a job as a bartender in the Hotel Diplomat in Times Square. I discover cognac and ditch all the other drugs.

Fortapache 1970-73: Short stories rejected, novels rejected. I’m divorced. Hack work and bartending pay the child support. An agent needs a writer for a movie about two cops who work the 41st, or “Fort Apache,” in the South Bronx. The cops keep putting his candidates through an ordeal by fear and alcohol and they all quit. I go to the Bronx. “You took the subway?” they ask in amazement. We go to a mob bar. They try to get me drunk, but I’m in training. After a few hours they’re so loaded that I dump my drinks on the floor and they don’t see. They drive me to the Bronx Zoo. Hookers patrol the perimeter. They get the biggest, fattest hooker into the back seat with me. This time my experience as a reporter pays off. I know how cheap cops are. “Is this on you guys?” I ask. They throw her out. I get the job.

1973: I write the first draft of Fort Apache, the Bronx for $1,250. The producers can’t sell it. Susskind reads it and says, “I’m going to make this movie.” I file the script and forget about it.

1973-75: Rejections and general dissipation.

1976: I finally learn how to write fiction well enough to get a novel published. I think the screenwriting taught me how to structure a story.

Rolling thunder 1976-78: An agent circulates Fort Apache in L.A. I get jobs on Baretta and Kojak but fight with the producers and Robert Blake and never finish the scripts. I write a pilot for John Houseman, which later becomes The Paper Chase. Bill Devane prevails on Larry Gordon to hire me to rewrite Rolling Thunder. I spend six riotous weeks in San Antonio. The laws of God and man are suspended on a movie location. The producer of Fort Apache hires me to adapt Ira Levin’s The Boys from Brazil. Six more great weeks, traveling super-first class in Lisbon, London and Vienna with Peck and Olivier. Susskind sells his company and gets financing for three movies. He calls me. “I’m going to do Fort Apache,” he says. I finally think it’s safe to quit my bar job.

The rest is war stories.

Me: Wow — what a saga! So tell me what life looks like now.

Heywood: Life is trying to turn out as much coherent work as I can before they put me in the Old Hack’s Home.

Me: I’ve got a question about how you’re putting out that work these days. Lately, all writers seem to be able to talk about is e-publishing. Yet it looks like The Serial Killer’s Daughter isn’t available as an e-book. Is that a temporary situation, or are you making a bold one-man stand against the Kindle and its ilk?

Heywood: It’s part of my agreement with the publisher. I maintain e-book rights and I promise not to put the book on Kindle until it goes into remainder. Kindle has been a boon for me. It’s revived a lot of my books that were out of print. I sell between 20 and 30 a month, and the number is inching up. I’m publishing all my books and have started a company, Tolmitch Press, to put up other worthy, forgotten titles. So far we have five new titles and are acquiring more. There’s no real money in it, but it’s great to give good books a new life.

Me: Obviously, publishing has changed a lot since you got your start. What do you think of the state of the industry? Are you in the “We’re the orchestra on the Titanic” camp or are you more hopeful?

Heywood: It’s always been a struggle for me to get a book published, so that hasn’t changed. The publishers that were content to give writers like me a small advance, take a share of the paperback and foreign sales and make an incrementally increasing profit as I took the 10 years to build up an audience are now non-performing divisions of industrial conglomerates. Their structure is no longer geared to the modest earner. They need a mega-hit to cover their overhead and justify their existence as the poor relation. They publish best-selling authors only and insist that they replicate their previous success by writing essentially the same book every time out. Marketers don’t innovate; they repeat a formula until it no longer works. Thus, the same tired heroes labor through 20 or 30 iterations of the same story until even their fans cry for mercy.

I could not follow my career chronology if I were a young writer today. The hundreds of magazines and scores of paperback publishers who kept so many of us alive no longer exist. It’s almost impossible to break into the movie business the way I did. Studios don’t make the kind of movies I was hired to write. Success was always based on luck colliding with talent. Now success is just a happy accident.

For me the future is with the small independents. Everybody wants to make money, but these people are in publishing because they love books. I sold my last two books by e-mail. Never met the publisher of Leading Lady [a thriller put out by Five Star in 2008] and just met the publisher of Serial Killer at the book launch. If I were a young writer today I might never be able to quit my bar job. But I’d keep writing anyway.

0 Responses to “Interview with Steve Hockensmith”