AUTOBAROGRAPHY

CHICKEN SALAD AND THE CLASS STRUGGLE

It was 1973. The Playboy Clubs were packing them in and it wasn’t for the Surf’n'Turf. Half-naked women serving highballs were all the rage. We called it “Chicken Smarmygiana” in the trade.

I was working at a place called “Maude’s” in the Summit Hotel on 51st. and Lexington. It was done up as a Gay Nineties, brothel. The eponymous Maude was a buxom store window dummy dressed as a madame with an electric eye that squawked “C’MON IN BOYS!” whenever a customer entered. The bartenders wore pleated shirts, red bow-ties and were issued one black garter, which management insisted they wear on their right sleeve. The waitresses squeezed into decollete spangled leotards and mesh stockings and teetered on spiked heels as they carried heavy drink trays. Hiring was democratic. Some girls made the costumes work. Others had you running for a raincoat.

I was the new man, so I had to open and work lunch. This meant getting up at nine-thirty, which for me was the crack of dawn. After I had stifled the staticky blast of the alarm, slid that fifty pound cement block off my chest and coughed up a cup of ashtray soup, the day started to get better. I had perfected the art of sticking my head under the shower without getting my shirt wet, which for me was the equivalent of a triple axel landing in a split. Most of my neighbors slept later than me so I could swipe the NY Times from a new door every morning. The 104 bus was a block away and I always got a seat. Now if I didn’t sleep past my stop and end up at the UN I would have it made.

Hotel security stood by the main entrance making sure all employees stayed out of the lobby. I was caught in a stream of chamber maids, cooks, clerks and janitors heading for the time clock.

Not a drop had been poured in that bar for twelve hours, plus it had been swabbed down with ammonia, but it still stank of cigarettes and stale beer. No problem. I made myself a French Kiss (cognac, kahlua, white mint and half and half.) In no time a warm feeling of well-being spread through me. Once in a while I’d find a dead mouse under the duck boards and twirl it by the tail to freak out the waitresses. I was suffering from what later became known as George W. Bush Syndrome–I thought I was just brimming with wit and charm. Nobody agreed, but I didn’t notice.

There was Marcy, a chunky Brooklyn brunette, who was always on the floor looking for a lost contact lens. “Hey, Marcy from Canarsie,” I ‘d say.

She’d look up sourly. “Hey, Dickhead from Schmuckville.”

Inga was tall, and Nordic with haunted Garbo eyes. “Inga, the Swedish Nightingale,” I called her.

“I’m Norwegian,” she said.

I wracked my brain. “Okay…Inga, the Broad from the Fjords…”

To this day I break into a cold sweat remembering her baleful look.

Monique was from Harlem. One afternoon after a few French Kisses I grabbed her hand. “Weird goddess, dusky as the night.”

She pulled away. “What’d you call me?”

“Dusky as the night,” I said. “It’s from a famous poem by Baudelaire.”

She slid a cocktail napkin across the bar. “Write that down…There better be a Baudelaire or my boyfriend’s gonna come down here and beat your ass.”

You could understand their sour moods. Lunch was an all-you-could-eat-serve-yourself buffet bar, $6.85, drinks and dessert extra. The specialite de la maison, Maude’s Famous Chicken Salad, dominated the table in a huge, gleaming silver tureen. It was the creation of Bob, the big, black gay chef, and was made with chicken chunks, Miracle Whip and Heinz Hamburger relish, studded with dried cranberries, apples, raisins and walnuts. People pushed and shoved to get to it and then piled it onto their plates out of spite. The waitresses only served drinks and coffees. As much as they wriggled and jiggled and giggled they still couldn’t get decent tips.

It was a union job, local 6, Hotel Workers. All that meant to me was a dues checkoff out of my check. I wasn’t planning to be around for the pension.

After I had been there a month, Red Eisenberg, the local’s Business Agent came to visit. If thugs hadn’t existed he would have had to invent them. He had a Cro Magnon head and walked like his species had only recently become erect. It was early February, but he was wearing a knit golf shirt and gray slacks. He rested his massive, freckled forearms on the bar

“What part of Brooklyn you from?” he asked.

How did he know I was from Brooklyn? “All over,” I said. “We moved a lot.”

“Why? Your father in the rackets?” He handed me a form. “Your health plan. Don’t get sick…”

On his way out he warned me: “Don’t make too much money. They’re watching you.”

I had been hired by Personnel and forced on Mr. Carney, the Food and Beverage Manager. He was from Oklahoma, a little guy with a blond comb over and wispy mustache. I heard him saying “when I was in the military” to Marcy one night and found out he had been a manager of the Officer’s Club at the Pensacola Naval base. I could imagine him hating the foreigners, the degenerates and the draft-dodgers he had under his command.

The kitchen help was mostly foreign, Hispanic, and Asian, who spoke halting English. Carney forced them to work extra shifts for straight time. He docked them for sick days. He didn’t provide locker space. The employee washroom was a disaster.

“He’s violating the contract ten times a day,” I said to Bob, the only American in the kitchen.

“If they’re too dumb to take care of themselves that’s their lookout,” he said.

The waitresses were constantly harassed. Somebody had drilled a hole in the wall of their dressing room. Customers pawed them and followed them after their shifts. Security wouldn’t help them, saying what did they expect if they walked around like whores.

I was ashamed of my own crude overtures. Of thinking that these ladies were fair game because of the costumes their exploitative employers made them wear.

“This place needs a shop steward,” I told Marcy. “Somebody to confront management. The union’s not doing enough.”

“The union’s protecting our jobs,” she said. “You’d have to blow the place up to get fired.”

But a week later I came to work to find a knot of anxious workers at the bar.

“Carney fired Mei,” Gus, the Dominican garde manger told me.

Mei was the Chinese dishwasher, the only one in a kitchen that turned out hundreds of covers and cocktails every day. I knew him as a a pair of splotched pants and stick-like arms behind three racks of washed glasses.

“You’re not a dishwasher, you’re a pearl diver,” I had told him once. After that he laughed whenever he came to the bar.

“No pearls today,” he would say.

Sometimes I would slip him a short beer. He would open his wallet and show me his daughter, who was playing cello in the Juilliard Youth Orchestra.

Why had Mei been fired?

“He was eating the chicken salad,” Gus said.

Every morning Bob would sculpt a mountain of chicken salad in the tureen and cover it with saran wrap with a big sign: “DO NOT EAT.” But when he returned to put it out he noticed the saran wrap disturbed and a huge gash cut into his mountain.

After Bob secretly complained, Mr. Carney had security install a hidden camera in the kitchen. They had caught Mei walking by lifting the saran wrap and jamming a handful of chicken salad into his mouth.

“So he was fired for eating chicken salad?” I said.

“For insubordination,” Marcy said.

“But did he even know about that rule?”

“The sign was clearly displayed,” she said.

“But does he even speak English?”

Carney came glaring to the door and everybody scattered.

I started cutting lemons, indignation boiling within me. Mei was the hardest worker in the place. You couldn’t see him behind that cloud of steam in the kitchen. He never missed a day.

They had all come to the bar to tell me. They were expecting me to do something, I could sense it.

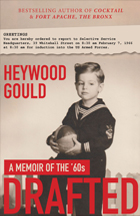

And why not? I was the same kid who had taken the bus to Washington in 1963 to cheer Martin Luther King. Who had walked picket lines and demonstrated for all kinds of causes. Who had protested the Vietnam War even after I was drafted.

In a second I had an idea. It was 10:30. Lunch started at 11. We didn’t have much time. I called the waitresses together and went into the kitchen.

“Are we gonna let the bosses get away with this?” I shouted.

Everybody stopped slicing and dicing.

” Let’s show solidarity with Mei.”

“How?” Gus asked.

“Let’s each take a bite out of their precious chicken salad. Right on their sneaky hidden camera. They can’t fire us all…”

Bob jumped at me on a panic, his cap quivering. “The man don’t want you to eat his motherfucking chicken salad, what’s the big deal?”

There were a few grumblers, but Gus quieted them in a torrent of eloquent Spanish.

“Form a line,” I shouted.

The waitresses looked at me with new respect.

“Okay,” I said, going to the head of the line. “Look right in the camera…”

I marched up, grabbed a handful of chicken salad and crammed into my mouth.

Everyone followed me, laughing, hugging and hi fiving, At the end, a few scraps of chicken salad were smeared in the bottom of the tureen.

“And we’ll do this every day until Mei is reinstated,” I shouted into the camera.

Everybody cheered as they went out to work.

Bob was busily cubing chickens. “Now I gotta make a whole new batch…”

Lunch was especially busy that day. But I could sense an elation and camaraderie in the air. I remembered what an old anarchist had told me:

“Collective action is the source of all human happiness.”

At two-thirty when the crowds thinned I saw Carney talking to Red Eisenberg at the door. Eisenberg came to the bar.

“Step outside with me for a second,” he said.

It was one of those all-weather winter days where the sun shines warm in one spot while the wind screeches in another, invisible snow flakes crinkle your face and cold shadows fall across the street.

A man in a dark overcoat was leaning against a gray Coupe De Ville parked in front of the hotel. He had a Florida tan and a mountain of coiffed white hair that reminded me for a second of Maud’s Famous Chicken Salad.

“This is Mr. Prinza, President of the union,” Eisenberg said.

“Who do you think you are, John L. Lewis, famous labor leader?” Prinza asked mildly. He lit a cigar with a gold Dunhill. “What part of Brooklyn do you come from anyway, the Russian neighborhood?”

“Just trying to save a man’s job,” I said.

“You incited an unauthorized work stopage,” Prinza said.

“This could cause them to tear up the contract and move to renegotiate,” Eisenberg said.

“Insubordination is grounds for dismissal in every labor agreement,” Prinza said.

“This guy hardly speaks English,” I said. “He should at least get another chance.”

Eisenberg shook his head. “He’s illegal. Working on somebody else’s Social Security card. He’s lucky they don’t throw his ass in jail.”

“He was stupid to break the rules,” Prinza said. “When you’re on the run you obey the speed limit.”

“There’s a lotta other people in that kitchen and busboys, who are illegal and supporting kids,” Eisenberg said. “You wanna open a can of worms they’ll all lose their jobs.”

I hadn’t thought of that. “It’s my fault,” I said. ” I started this. They should just fire me.”

Prinza flicked a big white ash off his cigar. “Don’t fall on your grenade, soldier. Nobody’s gonna get fired.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I just wanted to help this man…”

“Sometimes you gotta sacrifice the one for the many,” Prinza said.

In the silence I felt a strange sort of sympathy coming from both men.

“You payin’ alimony, kid?” Prinza asked.

It was as if he knew everything about me.

“You can get a good loan from our Credit Union,” Eisenberg said.

“Smoke cigars?” Prinza asked.

I shook my head, but he handed me a cigar anyway. ‘I’ll bet you’ve got an uncle who loves a good cigar…”

He even knew that.

“Go back to work, kid,” Prinza said. “And don’t feel so bad you won a major victory…

“Management says from now on you guys can eat all the chicken salad you want.”

.