MY FIRST PHYSICAL

Part 2

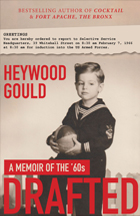

MY FIRST TRIP TO WHITEHALL STREET

It’s 1962 and the center is crumbling.

In Centralia, Pa. a garbage dump built over an old coal mine catches fire. The slow burning anthracite under the landfill is ignited and smolders unabated. The town is slowly consumed. The people endure heat, pollution and disease without protest.

In Union Square the Committee to Defend the Cuban Revolution preaches armed struggle against the US. The speakers are young and neat in dress shirts and pressed khakis–some even wear clip-on ties. They look over the heads of the crowd and speak through bullhorns in alien twangs–southern, mid-western.

“Resist the US Imperialist war against Social Democracy…”

An old man, trembling on a cane, warns: “Don’t sign their petition. It’s an FBI trick to get your names.”

A fat kid in overalls jumps off the platform and screams in his face. “All power to Fidel and Che and the brothers and sisters of the Revolution.”

The old man flinches but holds his ground. “Ask them who paid for the leaflets and the fancy loudspeakers.”

Across the park members of the Nation of Islam are handing out copies of their newspaper, “Muhammad Speaks.” Heads shaven, standing at attention in suits and bow ties, they surround their speaker like a Secret Service detail.

“Democracy and integration are the tools of the white oppressor,” he says. He advocates separation of the races and the establishment of black Muslim republics in the former Confederate states.

He is challenged by Mr. McManus, an elderly black Communist, veteran of the Spanish Civil War, who sells his mimeographed autobiography–”Brother Under Arms”–from a shopping cart.

“Segregation in any guise is just a ploy to fragment the working class and thwart the Revolution,” Mr. McManus says.

“Your revolution will never happen, my brother,” the speaker replies.

Mr. McManus’s voice cracks in frustration. “You don’t have the political, economic or military power…”

“Allah will liberate our people,” the speaker interrupts in implacable tones. “Your movement will be a footnote to history…”

Behind the speaker I see Andrew, a kid I’ve known since Brooklyn Technical High School. Just a week before we had split a reefer and gone to the Jazz Gallery to hear Gil Evans. I wave. He stares through me without recognition.

Attorney General Robert Kennedy has announced a campaign to crack down on Organized Crime. He has proposed legislation to make gambling a federal offense.

“It’s a message to the Syndicate,” explains Sal, the bartender at the Park Circle Lanes, across the street from the Brooklyn Riverside Memorial Chapel. “He don’t want them to think they own the White House just because old man Kennedy was partners with the bootleggers.”

Sal has a mountain of prematurely white hair, each ridge carefully tended, over thick black eyebrows and black eyes. He’ll make you a drink, take a number, book a bet, lend you money–anything you want. On Ladies League Night you can’t get near the bar. Housewives on their night out drink Seven and Sevens and Whiskey Sours . “Hey Sal, how come you never bring your wife around?” one of them flirts.

“Why take a ham sandwich to a banquet?” Sal says and they screech with laughter.

Sal’s “gummare” Diane sits at the end of the bar. “Her husband’s upstate on a business trip,” Sal confides with a wink. “An eight year business trip.”

Diane’s got a blonde beehive, wingtip glasses, boobs jutting like cow catchers, capri pants and mules– a style that has tormented me since puberty. She smokes Kools, leaving lipstick smears on the cork tips. She has a way of sucking on the cigarette that drives me to demonic masturbation.

I run back to the chapel looking for a free bathroom and am confronted by an old man in a prayer shawl.

“It’s a shandeh (shame) what’s going on here,” he says.

It’s Mr. Wolfe, a “watcher,” hired by Orthodox Jews to sit all night before the funeral and recite Psalms for the deceased.

“I found a policeman on the sofa,” he says. “Shoes off, gun on a chair, sleeping in the same room as the departed. I asked him to leave and he said the person was dead, he wouldn’t care if Hitler was in there…”

“The cops don’t understand,” I say.

“Hashem (God) looks at the sin, not the reason,” Mr. Wolfe says. He digs his nail into my wrist and whispers harshly. “I’m coming here twenty-five years. Police came in and slept. They even brought women. But they never did it in a room with a soul whose fate has not been decided. They had respect for the dead…”

I play the numbers with Sal, a dime a play. With a 500 to 1 pay off I can make fifty bucks if I hit, minus the two-fifty vig. One night Sal slips a five into my hand.

“I’m givin’ you a refund ’cause you’re such a good customer,” he says. “But you gotta do me a favor, okay.” He points down the bar to a swarthy, morose lady staring into a cup of coffee.

“That’s Terry, Diane’s sister-in-law. She brings her in to make everything look kosher. But tonight her car’s in the shop. Could you drive her home.”

In the garage police cars are blocking the station wagons, but they’ve left the keys so I move them out of the way.

Terry is waiting outside the bowling alley. She presses against the door, sitting as far away from me as she can.

“I live on E.19th. and Ave. R,” she says.

She’s silent for a while. She looks out of the window, but I get the feeling she’s watching me.

“Workin’ your way through college?”

“Yeah…”

“Medical school?”

That would be too big a lie. “Dental,” I say.

“My girlfriend Camille married a dentist. Artie Levinson. He’s a good provider. Gave her a mink for her birthday…The family was against it but now they love him. He fixes everybody’s teeth for free…”

It’s a dark street.

“You can pull into the driveway,” Terry says.

There’s a light on in her house.

“My daughter must be home,” Terry says. “She’s starting at St. Francis next year.”

Oh great, I think, she’s going to introduce me to her swarthy, morose daughter. Instead she reaches out and puts her hand in my lap.

“Can you keep a secret?” she asks.

She slides over next to me and unbuttons her bowling shirt. No bra. I almost lose it.

“How old are you?”

“Nineteen…”

“Nineteen,” she says and repeats “nineteen, nineteen,” as if it’s a magic mantra.

I’m usually done before the zipper is down. This time I grit my teeth and think about baseball. But I don’t make it past the first inning.

A few nights later I go into the bowling alley and am greeted by Sal.

“Hey kid, how’s the Revolution?”

I panic. How does he know about my secret political life?

“Revolution?”

“Yeah you know, 1776? Terry says you’re a regular Minute Man…” He laughs. “Now you know. Broads talk, too.” He slides me a triple shot of J&B. “Next time have a few of these. It’ll make you last longer.”

A few hours later I’m puking between cars on the D train to Manhattan. I see a piece of pepperoni from a slice of pizza I’d had a few days before.

At nine the next morning I go downtown to Selective Service headquarters on Whitehall Street. It’s across from Bowling Green where Rip Van Winkle took his twenty year nap There must be a couple of hundred kids. A guy in a khaki uniform is at the door.

“Down the hall…”

We enter a large room with picnic tables. An older guy in a white shirt with a lot of ribbons repeats:

“Take a form and a sharp pencil, find a seat and and fill it out…Take a form and a sharp pencil, find a seat and and fill it out.”

In the front of the room a man with a khaki shirt with red Sergeant stripes and blue pants with a stripe down the middle says in a loud, ringing voice:

“This ain’t the prom, gentlemen. Don’t look for a dancing partners. Just find a place to sit and fill out the form. Answer all the questions. Print clearly and legibly. Make sure you check in the boxes. The quicker you do this, the quicker you get out of here.”

A big, shaggy kid gets up and lumbers toward the door.

“Where you goin’, sir?” the Sergeant asks.

“Lookin’ for the bat’room.”

“Sit down and finish the form.”

The big kid keeps walking. “If I sit down I’ll piss in my pants.”

“If you piss in your pants make sure you save enough for your urine specimen or you’ll have to take the physical all over again.”

The kid sits down.

NEXT: THE PHYSICAL